Ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement, is more than simply placing flowers in a vase—it is a discipline that expresses harmony, balance, and the beauty of nature. Among the many schools of ikebana, three are especially influential: Ikenobo, Ohara, and Sogetsu. Each has its own unique philosophy, history, and style, ranging from classical elegance to modern creativity. For beginners, travelers, and cultural enthusiasts, learning about these three major schools offers a fascinating gateway into one of Japan’s most refined traditional arts.

What is Ikebana? The Charm of Japan’s Traditional Culture

The Essence and Spirit of Ikebana

Ikebana, often translated as the Japanese art of flower arrangement, goes far beyond decoration. At its core, it is about expressing the harmony between humans and nature through the act of “giving life to flowers.” Each arrangement reflects seasonal awareness, balance, and simplicity, values deeply rooted in Japanese aesthetics. The placement of each stem, leaf, and blossom carries meaning, symbolizing not only the natural beauty of plants but also a philosophical view of impermanence, space, and harmony. Practitioners approach the work with mindfulness, seeing it as a spiritual practice that cultivates patience, discipline, and appreciation for subtle beauty.

Differences and Similarities with Tea Ceremony and Calligraphy

Ikebana is often mentioned alongside tea ceremony (sadō) and calligraphy (shodō) as one of the “three classical arts of refinement” in Japan. All three share a focus on mindfulness, discipline, and the pursuit of inner harmony through a structured practice. However, ikebana is unique in its direct engagement with living materials—flowers, branches, and leaves—making each creation ephemeral and tied to the changing seasons. Unlike calligraphy, which captures permanence in ink, or tea ceremony, which creates a shared moment through ritual, ikebana emphasizes transience and transformation. Together, these arts embody the Japanese idea that everyday acts, when performed with intention, can become profound expressions of beauty and philosophy.

The Three Major Schools of Ikebana

Ikenobo (池坊)

Ikenobo is considered the oldest and most prestigious school of ikebana, with origins tracing back to the 15th century at the Rokkaku-dō temple in Kyoto. It is regarded as the birthplace of ikebana as a formalized art. The school developed the “Rikka” (standing flowers) style, characterized by tall, elaborate arrangements symbolizing landscapes in miniature. Later, it introduced the more simplified “Shōka” (living flowers) style, which emphasizes balance and natural beauty with fewer elements. Ikenobo is known for its formality, tradition, and focus on spiritual refinement, making it central to the history and philosophy of ikebana.

Ohara-ryu (小原流)

Founded in the late 19th century during the Meiji era, the Ohara School brought innovation by introducing the “Moribana” (piled-up flowers) style. This technique places flowers in wide, shallow containers, allowing for more naturalistic and expansive arrangements that reflect landscapes and seasonal scenes. Ohara-ryu emphasizes harmony with nature and often incorporates seasonal flowers, grasses, and branches to evoke the beauty of Japan’s changing environment. The school is also recognized for its openness to modern aesthetics and accessibility, making it popular among beginners and those looking for a slightly less rigid style of ikebana.

Sogetsu-ryu (草月流)

The Sogetsu School, founded in the 20th century, is celebrated for its modern and highly creative approach. Unlike the more traditional schools, Sogetsu teaches that ikebana can be done “anytime, anywhere, by anyone, with any material.” This philosophy embraces not only flowers and plants but also unconventional materials such as metal, glass, and plastic. Its works often resemble modern art installations, bridging ikebana with contemporary design. With strong international outreach, Sogetsu has inspired ikebana enthusiasts around the world and remains a leading force in presenting the art as both timeless and evolving.

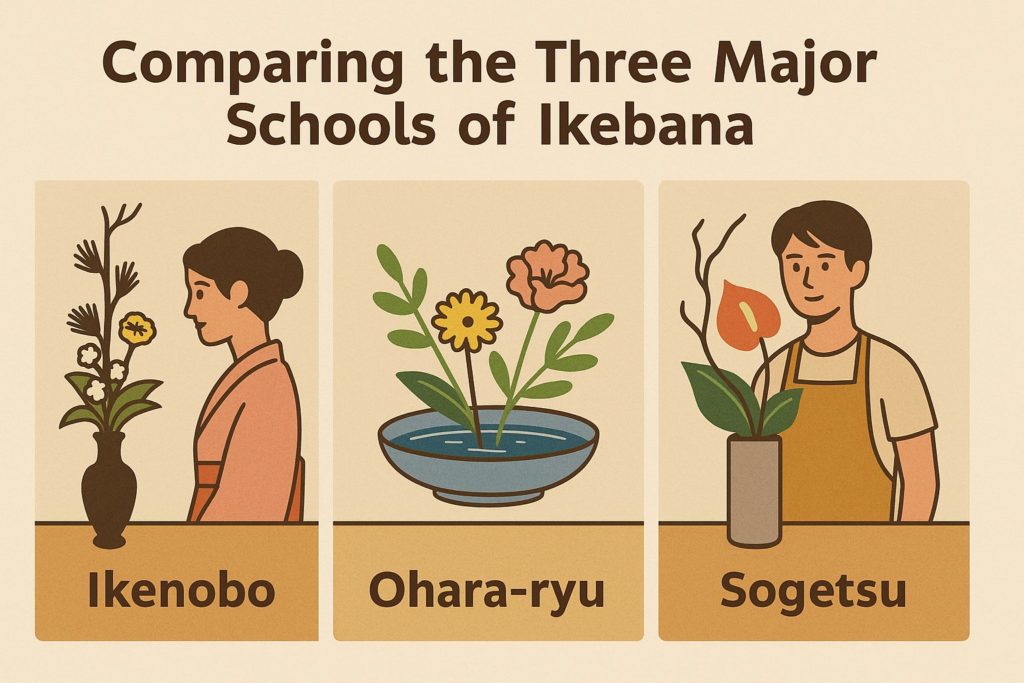

Comparing the Three Major Schools of Ikebana

Differences in Expression Styles

The three major schools of ikebana each emphasize a distinct approach to expression. Ikenobo values formality and tradition, with highly structured arrangements that reflect centuries of refinement. Ohara-ryu focuses on natural beauty, often arranging flowers in ways that mirror seasonal landscapes or natural scenery. Sogetsu-ryu, in contrast, champions free expression, encouraging artists to experiment with space, form, and unconventional materials. Together, these styles represent the spectrum of ikebana—from classic elegance to modern artistic innovation.

Selection and Characteristics of Materials

Each school also differs in how it chooses and uses materials. Ikenobo tends to favor traditional plant materials such as pine, plum, and seasonal flowers, which symbolize classical Japanese aesthetics. Ohara-ryu makes full use of seasonal plants—wildflowers, branches, and grasses—to highlight the beauty of nature’s transitions. Sogetsu-ryu expands the palette far beyond plants, incorporating metal, glass, driftwood, or even industrial objects. This flexibility reflects Sogetsu’s philosophy that ikebana can be created “anywhere, anytime, with any material.”

Recommended Schools for Beginners

For beginners, choosing a school often depends on personal interests and lifestyle. Ohara-ryu is often recommended for those who enjoy seasonal flowers and naturalistic styles, making it approachable for first-timers. Sogetsu-ryu appeals to those with a creative or artistic background, as it encourages experimentation and does not impose strict rules. Ikenobo, while more formal, offers a deep connection to tradition and history, making it ideal for learners who appreciate structure and cultural heritage. Ultimately, the “best” school depends on whether a beginner values tradition, nature, or creativity as their starting point.

How to Experience Ikebana

Lessons and Trial Classes

For those who want a hands-on introduction to ikebana, many schools and cultural centers in Japan offer trial lessons and short-term workshops. In Tokyo, you can find classes through cultural facilities, ikebana schools (Ikenobo, Ohara, Sogetsu), or even international community centers that provide English-speaking instruction. In Kyoto, the historical home of Ikenobo, visitors can join beginner-friendly workshops at temples or dedicated studios. Trial lessons usually last one to two hours, allowing participants to learn basic techniques and create a small arrangement they can take home or photograph as a memory.

Events and Exhibitions

Ikebana can also be experienced through exhibitions and seasonal events. Each major school hosts large-scale Ikebana exhibitions (ikebana-ten) in cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka, where hundreds of works are displayed in modern halls or traditional venues. These exhibitions highlight both classical and avant-garde arrangements, giving visitors a wide perspective on the art’s diversity. Overseas, schools like Sogetsu and Ohara frequently hold demonstrations and workshops, spreading Japanese flower art worldwide. Attending such events allows visitors not only to admire the artistry but also to understand how ikebana continues to evolve in contemporary society.

Qualifications and Certification Systems

For learners who wish to go beyond a one-time experience, each school offers formal certification programs. Students progress through levels, earning diplomas or licenses that acknowledge their skills and allow them to teach in the future. For example, Ikenobo and Ohara have long-established systems of licenses, while Sogetsu’s programs emphasize creative development alongside structured study. Gaining certification can take years, but for many, it becomes a rewarding cultural pursuit and even a professional career path. This system ensures that ikebana is preserved, passed down, and continually reinvented for future generations.

The Future and Global Expansion of Ikebana

Popularity and Activities Overseas

Ikebana has long since crossed Japan’s borders, with active chapters and study groups in more than 50 countries worldwide. Major schools such as Ikenobo, Ohara, and Sogetsu maintain overseas branches, offering workshops, exhibitions, and certification programs abroad. Ikebana International, a global organization founded in 1956, also promotes cultural exchange by bringing together practitioners from different schools. Today, many universities, cultural institutes, and Japanese embassies host ikebana demonstrations as part of cultural diplomacy, highlighting how flower arrangement fosters cross-cultural understanding and appreciation of Japanese aesthetics.

Fusion with Contemporary Art

In recent decades, ikebana has increasingly engaged with the world of modern art and design. The Sogetsu school, in particular, has pioneered collaborations with architects, fashion designers, and contemporary artists, creating large-scale installations that resemble sculptures or environmental art. Ikebana artists often present works in museums, galleries, and public spaces, where the boundaries between tradition and innovation are intentionally blurred. This fusion keeps ikebana relevant in the modern era, showing that its principles of harmony and creativity can adapt to new contexts while still honoring centuries-old traditions.

Significance as Part of Japanese Culture

Despite its evolution, ikebana remains a vital part of Japan’s cultural identity. It is valued not only as an art form but also as a practice that nurtures mindfulness, appreciation for nature, and respect for tradition. Schools and practitioners are working actively to pass the art on to younger generations, offering trial lessons for children, integrating ikebana into school programs, and adapting styles to modern lifestyles. In this way, ikebana continues to embody the Japanese philosophy of finding beauty in simplicity and transience, ensuring that it will remain a living tradition for the future.